150,000-Year-Old Jewelry Represents Earliest Form of Widespread Human Communication

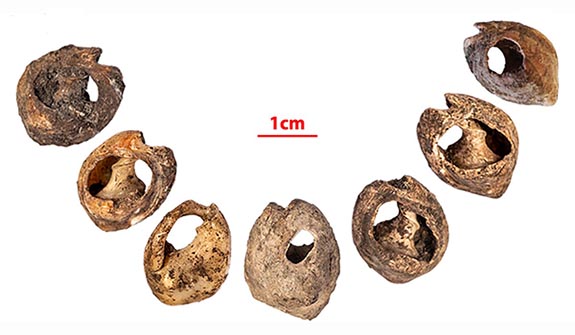

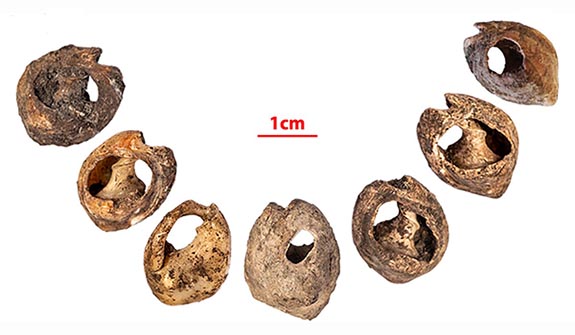

An international team of archaeologists believe the 33 shell beads recovered from a cave in western Morocco represent the earliest known evidence of a widespread form of nonverbal communication among humans.

Measuring about a half-inch across and drilled to be hung on a necklace, the beads made from sea snail shells have been dated at 142,000 to 150,000 years old.

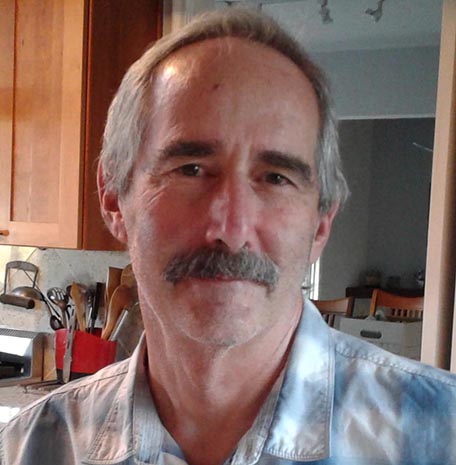

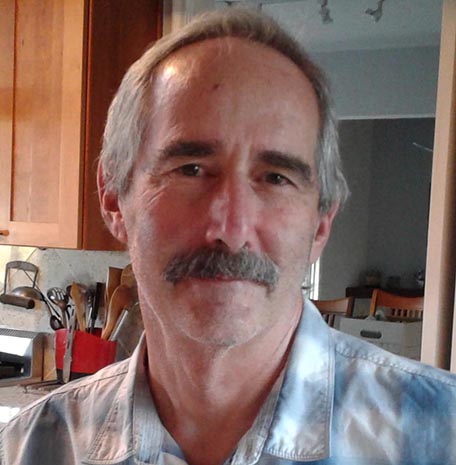

"We don't know what they meant, but they're clearly symbolic objects that were deployed in a way that other people could see them," said Steven L. Kuhn, a professor of anthropology in the University of Arizona College of Social and Behavioral Sciences.

The professor believes the beads were part of the way people expressed their identity with their clothing.

"They're the tip of the iceberg for that kind of human trait," he added. "They show that it was present even hundreds of thousands of years ago, and that humans were interested in communicating to bigger groups of people than their immediate friends and family."

Kuhn and an international team of archaeologists recovered the 33 beads from the Bizmoune Cave between 2014 and 2018. Their findings were detailed this past Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

Kuhn co-directs archaeological research at the cave with Abdeljalil Bouzouggar, a professor at the National Institute of Archaeological Sciences and Heritage in Rabat, Morocco, and Phillipe Fernandez, from the University Aix-Marseille in France, who are also authors on the study.

El Mehdi Sehasseh, a graduate student at the National Institute of Archaeological Sciences and Heritage, who did the detailed study of the beads, is the study's lead author.

The archaeologists noted that other, similar beads have been found at sites in northern and southern Africa, but previous samples date back to no older than 130,000 years.

The beads found in western Morocco are linked to the Aterian people of the Middle Stone Age. They were known for their distinctive stemmed spear points, with which they hunted gazelles, wildebeest, warthogs and rhinoceros, among other animals.

The scientists believe the beads may have served as a lasting form of communication, unlike the practice of painting their bodies or faces with charcoal or ochre. One theory involves how the Aterian people may have reacted to a growing population. As more people began occupying North Africa, they may have needed new ways to identify themselves with jewelry.

"It's one thing to know that people were capable of making [the shell jewelry]," Kuhn said, "but then the question becomes, 'OK, what stimulated them to do it?'"

Credits: Dig site image courtesy of Steven L. Kuhn. Shells image courtesy of Abdeljalil Bouzouggar. Steven L. Kuhn image / Supplied.

Measuring about a half-inch across and drilled to be hung on a necklace, the beads made from sea snail shells have been dated at 142,000 to 150,000 years old.

"We don't know what they meant, but they're clearly symbolic objects that were deployed in a way that other people could see them," said Steven L. Kuhn, a professor of anthropology in the University of Arizona College of Social and Behavioral Sciences.

The professor believes the beads were part of the way people expressed their identity with their clothing.

"They're the tip of the iceberg for that kind of human trait," he added. "They show that it was present even hundreds of thousands of years ago, and that humans were interested in communicating to bigger groups of people than their immediate friends and family."

Kuhn and an international team of archaeologists recovered the 33 beads from the Bizmoune Cave between 2014 and 2018. Their findings were detailed this past Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

Kuhn co-directs archaeological research at the cave with Abdeljalil Bouzouggar, a professor at the National Institute of Archaeological Sciences and Heritage in Rabat, Morocco, and Phillipe Fernandez, from the University Aix-Marseille in France, who are also authors on the study.

El Mehdi Sehasseh, a graduate student at the National Institute of Archaeological Sciences and Heritage, who did the detailed study of the beads, is the study's lead author.

The archaeologists noted that other, similar beads have been found at sites in northern and southern Africa, but previous samples date back to no older than 130,000 years.

The beads found in western Morocco are linked to the Aterian people of the Middle Stone Age. They were known for their distinctive stemmed spear points, with which they hunted gazelles, wildebeest, warthogs and rhinoceros, among other animals.

The scientists believe the beads may have served as a lasting form of communication, unlike the practice of painting their bodies or faces with charcoal or ochre. One theory involves how the Aterian people may have reacted to a growing population. As more people began occupying North Africa, they may have needed new ways to identify themselves with jewelry.

"It's one thing to know that people were capable of making [the shell jewelry]," Kuhn said, "but then the question becomes, 'OK, what stimulated them to do it?'"

Credits: Dig site image courtesy of Steven L. Kuhn. Shells image courtesy of Abdeljalil Bouzouggar. Steven L. Kuhn image / Supplied.